by Certified NPO Development Education Association (DEAR)

by Certified NPO Development Education Association (DEAR)

What is adult learning / education?

Japanese Adult Learning and Education (ALE)

How is adult education developed in Japan?

● Haruhiko Tanaka Tanaka Haruhiko

Adult education is called social education or lifelong learning in Japan. Social education is an educational and learning activity in a society other than school education and home education, and includes youth work in addition to adult education. (Figure 1)

Social education under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology is operated based on the Social Education Law enacted in 1949 (Showa 24). Public halls, libraries, museums, youth facilities, lifelong learning centers, etc. are engaged in social education projects. In other ministries and agencies, departments in charge of social welfare, environment, gender equality, international exchange, employment, etc. provide programs related to adult education.

In the private sector, traditional community organizations (youth groups, women's associations, self-governing associations), non-profit NPOs, commercial culture centers and community colleges, distance learning, etc. are developing business and activities related to adult education. In addition, the Open University of Japan provides lectures using the media, and many universities have open lectures for citizens and admission systems for working adults.

There are five main contents of adult education. The first is learning for profession and qualifications. This is an educational and learning activity aimed at acquiring the knowledge, skills and qualifications necessary for a profession. The second is learning for self-sufficiency, where hobbies, sports, entertainment, etc. are included. Here, learning activities are not a means, but an end in themselves. Third is learning for daily life and life cycle. It is a learning activity that is carried out at a turning point in life and is related to job hunting, marriage, housework, child-rearing, retirement age, etc. Fourth is the learning necessary for civic activities. Includes learning related to volunteer activities, neighborhood associations / residents' associations, SDGs, etc. Fifth is supplementary lessons. This is equivalent to literacy education for those who have not received sufficient school education. Currently, it is also being developed as a learning activity for foreigners who have not received Japanese school education. Much of adult education in developing countries is done as literacy education for adults.

Lifelong Learning, which is widely used along with social education, refers to the idea of building an educational system that enables learning activities at school and in society from birth to death (Fig. 2). Lifelong learning covers both school education / social education for young people and school education (recurrent education) / social education for adults. When we talk about adult education, we mean the latter. According to the Lifelong Learning Promotion and Development Act of 1991 (Heisei 3), Lifelong Learning Centers were established in each prefecture.

Figure 1 Classification of home education, school education, and social education

Figure 2 Adult education in lifelong learning

What kind of adult education support does Japan provide?

● Takashi Miyake Miyake / Takafumi / Rie Koarai Koarai / Rie

1. Support for adult education through Official Development Assistance (ODA)

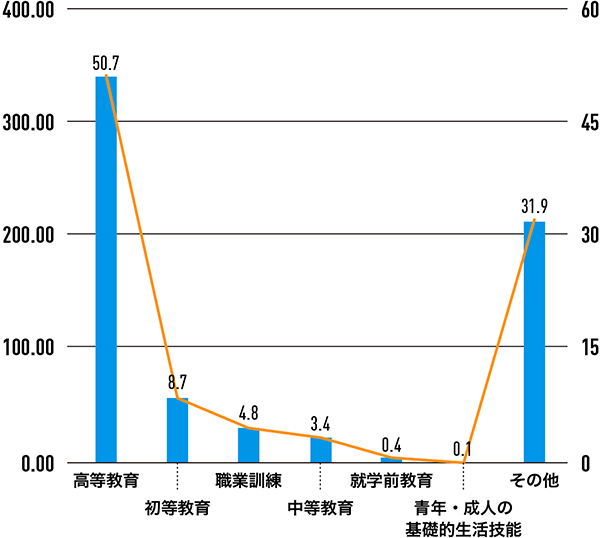

As can be seen from the graph in Fig. 1, education assistance to developing countries through Japan's ODA is focused on higher education assistance. Literacy education support that teaches reading, writing and calculation of letters to young people and adults who did not have sufficient opportunities to receive education is classified as "basic life skills of young people and adults", but the amount of educational support by Japanese ODA Only 0.1% of the total. In addition, the amount of vocational training assistance is limited to 4.8%.

Figure 1 Average amount of Japan's Official Development Assistance 2014-2018 ($ 1 million, left) and percentage of educational assistance (%, right)

Source: Created based on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs website https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/gaiko/oda/bunya/education/statistic.html (OECD / DAC CRS online database promised amount base)

Non-formal education refers to organized activities that take place outside the formal school education system and provide important learning opportunities for children, young people and adults who have not had the opportunity to go to school or have dropped out of school. increase. For non-formal (out-of-school) education support including literacy and technical training conducted by Japanese ODA, for example, literacy and non-formal that the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), which is the implementing agency of ODA, has implemented in Pakistan and Afghanistan. There is educational support. In Pakistan, where 41% of young people and adults over the age of 15 are unable to read and write, and there are 22.8 million children who cannot go to school, in addition to dispatching Japanese experts, children who have not been able to go to school since 2004 Establishing a non-formal education system through comprehensive activities such as non-formal basic education and literacy education curriculum for adults, teaching materials, training modules, evaluation methods for learning achievement, database development, etc. I did. From 2015, the target area will be expanded, and from 2021, in addition to adult literacy and technical training, primary education for preschool children and young people and lower secondary education (Japanese junior high school) level learning will also be available. To promote it, support projects have begun that include activities such as the development, revision and introduction of curriculum, teaching materials and evaluation methods, data-based management, strengthening collaboration among stakeholders and support for policy formulation.

Afghanistan is in a complex and protracted crisis of more than 40 years of conflict, natural disasters and, more recently, coronavirus infections, and many grow up without proper education. To do. Of the young people and adults aged 15 and over, 43% can read and write, especially women (29.8%), which is a serious problem. JICA supported the establishment of a community learning center for non-formal educational activities such as literacy and technical training for young people and adults from 2004 to 2007, and the ability of the literacy bureau of the Ministry of Education of Afghanistan from 2006 to 2008. We provided support to provide literacy education opportunities to 10,000 non-literate people through strengthening and NGOs. Furthermore, from 2010 to 2018, in order to improve the quality of literacy education, we also provided support for the purpose of strengthening administrative capacity so that the literacy bureau can properly monitor literacy education. Specifically, monitoring of literacy classes, evaluation of how much literacy skills learners have acquired, development of guidelines and tools for collecting and reporting data such as the number of classrooms, teachers, and learners, and all of Afghanistan. We conducted training for literacy bureau staff in 34 prefectures and Kabul city together with the literacy bureau, and contributed to the institutionalization of various tools as a country.

In this way, JICA's literacy and non-formal education support is literacy as a country, including educational programs supported by other organizations such as NGOs, where the government of the country itself appropriately conducts educational activities, monitoring and evaluation. We are cooperating with a focus on building systems and strengthening administrative capacity so that the quality of non-formal education can be ensured.

(Related materials) ・ Japan International Cooperation Agency International Cooperation Training Institute (2000) “Toward the expansion of non-formal education support” https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/11788767.pdf

・ JICA website https://www.jica.go.jp/project/pakistan/003/outline/index.html

And https://www.jica.go.jp/project/pakistan/008/outline/index.html

・ Rie Koarai and Taeko Takayanagi (2016) “Chapter 14 Literacy / Nonformal Education” edited by Taro Komatsu “Education and Development in the World in Developing Countries” Gyosei, 2016 ・ Education Cooperation NGO Network (2017) “Japan's Education Cooperation NGO Contribution to SDG4 by ” http://jnne.org/doc/contribution_of_japanese_ngos_to_sdg4_ver2.pdf

2. Support for adult education by NGOs

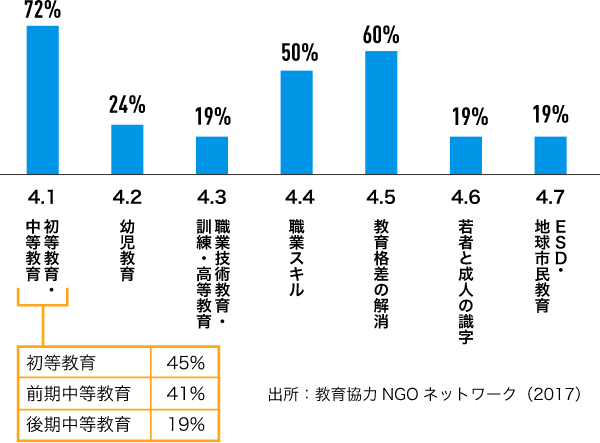

Of the approximately 500 international cooperation NGOs in Japan, 70% are the most active in the field of education, and approximately 350 organizations are implementing educational cooperation projects. According to the results of a survey of 58 educational cooperation projects in 2017, in the field of adult education, vocational skills are 50%, youth and adult literacy is 19%, and ESD is 19% (Fig. 1). According to a 2006 survey of 214 educational cooperation projects, formal education accounted for 53%, while non-formal education accounted for 47%. Therefore, the characteristics of adult education support by Japanese NGOs are as follows: (1) Emphasizing vocational skills and literacy compared to the above-mentioned Japanese ODA, and (2) Supporting adult education through non-formal education as well as school education. You can give what you are doing.

Figure 2 Contribution of each target of SDG4 of educational cooperation project by NGO (58 projects / multiple answers)

There are two good examples of adult education support. First, the National Federation of UNESCO Associations of Japan started the "World Terakoya Movement" in the wake of the 1990 International Literacy Day. Community learning centers in Asian regions such as Cambodia, Afterganistan, Nepal and Myanmar are strengthening their ability to develop literacy, vocational and livelihood improvement skills in line with local learning needs.

Second, the Shanti Volunteer Association targets internally displaced persons and women aged 15 and over who are displaced from Pakistan and elsewhere as part of the emergency humanitarian assistance provided in Afghanistan from June 2019 to July 2020. We conducted literacy education (150 people) and sewing technical training (75 people). In March 2020, all educational facilities were closed by the government due to the spread of the new coronavirus infection, but in accordance with the Ministry of Education's corona response plan, 5 students per class outdoors to prevent infection. The classroom was continued by taking advantage of the flexibility that is characteristic of non-formal education such as learning form, place and time. As a result, all 150 literacy learners were awarded a certificate equivalent to a third grader by the State Department of Education. Also, in the sewing class, women made masks to prevent infection, but plans were made to sell the masks to villagers at a low price and use them for women's empowerment activities if they make a profit. The activity was continued by the local residents even after the support by Shanti was completed.

(Related Documents)

・ Takashi Miyake and Rie Koarai (2019) “Chapter 11 International Educational Cooperation by NGOs” Nobuko Kayashima and Kazuo Kuroda ed. “History and Prospects of International Cooperation in Japan” Tokyo University Press, 2019 ・ Rie Koarai (2021) Chapter 51 NGO Support Activities ”edited by Kosaku Maeda and Kazuya Yamada,“ 70 Chapters for Understanding Afghanistan ”Akashi Shoten, 2021 ・ Educational Cooperation NGO Network (2017)“ Contribution to SDG4 by Japanese Educational Cooperation NGOs ” http //jnne.org/doc/contribution_of_japanese_ngos_to_sdg4_ver2.pdf